By Chris Mooney, Energy and Environment, The Washington Post

The water situation in California is getting downright scary. Last week, the Department of Water Resources found “no snow whatsoever” in its Sierra Nevada snowpack survey and Gov. Jerry Brown declared mandatory reductions in water usage in the state. In particular, the more than 400 agencies supplying water to urban areas will have to cut total usage by 25 percent below 2013 levels.

You might think this means draconian rules and rationing — telling people they can’t water their lawns most days of the week, for instance. And there will, most assuredly, be such enforced measures.

But a crucial part of the savings, especially for more innovative water districts, may not have to be mandatory at all, say several California water experts. Instead, savings can emerge from finding more voluntary ways to change people’s water-use habits and behaviors. That may include both pricing water differently, especially beyond a certain base level of use, and also “nudging” people, in the popular parlance of behavioral economics, to adopt different water-use behaviors.

When it comes to changing people’s water-use habits, “we think that’s the biggest way that we will achieve the savings that we need during the drought,” says Peter Brostrom, the water-use efficiency section chief at the California Department of Water Resources. Indeed, a recent presentation by Long Beach Water, which has been a leader in cutting water use — claiming a 34 percent reduction in the Long Beach, Calif. area since the 1980s — emphasizes that “behavior change is key to our past and future success.”

The first key innovation involves pricing water differently. Indeed, the governor’s executive order explicitly calls for water utilities to adopt “rate structures and other pricing mechanisms” that will drive more conservation.

One of the most interesting pricing ideas out there has already been adopted by the Irvine Ranch Water District in Orange County, Calif., which says it has achieved “a 156 percent greater savings than would have occurred if the District had implemented mandatory two-day per week watering restrictions only.” The approach involves setting “water budgets” or, more wonkily, an “allocation based conservation rate structure,” based on the individual characteristics of homes in an area.

Such budgets typically take into account factors such as home and family size, outdoor landscaping area and area climate. Then utilities charge quickly escalating prices per unit of water once the household gets beyond what is deemed to be an “efficient” level of use.

“We’ve seen more and more interest in this kind of rate structure over the last decade and since the late 2000s,” says Ellen Hanak, an economist who directs the Public Policy Institute of California. Hanak says an approach that considers the individual circumstances of each home is much preferable to a blunter one in which prices rise in the same way for everyone as use levels increase, because it does a better job of rewarding people for being water-efficient.

It has also been shown to work. In a study recently published in the journal Land Economics (earlier draft here), Kenneth Baerenklau of the University of California at Riverside and two colleagues demonstrated big water savings with such an approach.

The researchers studied Southern California’s Eastern Municipal Water District, which switched over to water budgets in April 2009, putting in place a pricing structure that took into account various household factors in setting budgets and then charged much more for water use deemed “excessive” or “wasteful.” Using data provided by the utility, the study tracked the accounts of 13,565 water users to see how they behaved before and after the launch of the new pricing system. It found that after the new prices took effect, water demand dropped steadily, so much so that it was 17 percent lower after three years.

There’s one drawback in the current drought context, however. “The effect was not immediate,” explains Baerenklau. It played out gradually over three years. So if utilities want really fast changes to comply with the governor’s order, changing pricing, alone, may not be enough.

Still, Baerenklau says, it makes a great deal of sense. “Historically, there has been a lot of prescriptive mandates” to get Californians to use less water, he notes, “but there’s good economic reasons to pursue flexible, incentive-based approaches.”

And that’s not the only non-mandatory method that has been demonstrated to reduce people’s water use. Another approach involves taking a page from the electric utility industry, which for some time has been implementing behavioral programs to get people to use less power — programs that have shown documented success.

“The energy utility space tends to move a little bit ahead of the water space,” says Edward Spang, associate director of the Center for Water-Energy Efficiency at the University of California at Davis. “There’s a lot of study on behavior based energy conservation, and people are now studying the water implications of behavior based conservation.”

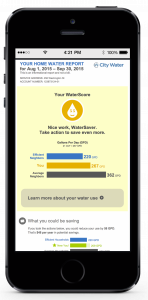

If you talk to California water-policy types about changing people’s behaviors and habits, it isn’t long before you hear about the company WaterSmart Software, which provides individualized home water reports reminiscent of the better-known home energy reports provided by Opower, a customer engagement firm that works with electric utilities. WaterSmart, for its part, works with water utilities and providers and currently has 38 clients across the United States, about 80 percent of them in California, says spokesman Jeff Lipton.

The reports, which combine utility-provided data about individual water use with an analysis of property records to get a sense of home layout and yard size, not only tell people how much water they’re using — in useful units like gallons, and also dollars and cents — but, critically, how their usage compares to that of their neighbors. Thus, the reports leverage the tried-and-true power of peer pressure and social norms to get people to use less water.

Here’s an example of a mobile version of a WaterSmart report (they are also sent by regular snail mail):

It’s not just the peer comparison. The reports also tell people where they’re using water in their homes and how they can cut back, and connect them with water-saving programs that their utilities are running.

In an independent 2013 analysis of consumers receiving WaterSmart’s reports in the East Bay Municipal Utility District, two groups of customers receiving the reports saved 4.6 and 6.6 percent more water than members of control groups who did not receive reports. The company itself claims the ability to reduce usage by 5 percent, which is consistent with these figures.

“What you’re doing is you’re pushing for water conservation purely with better information for people,” says Spang. “So it can be implemented rapidly and it can be implemented widely.”

Only a fraction of California’s water utilities currently use this program, says WaterSmart’s Lipton, although he also adds of the worsening drought, “This will certainly generate more business for us.”

The non-mandatory approaches don’t end there. Utilities will also certainly be offering more price incentives to get people to swap out less water-efficient appliances, such as washing machines and dishwashers, says Andrew Fahlund, deputy director of the California Water Foundation. And for the cheaper stuff, they might even give it away.

“We’ll probably see a lot of utilities even giving away low-flow shower heads, or even helping people install them and that kind of thing,” he says. EPA-certified low-flow shower heads can save 2,900 gallons annually for a typical family, the agency says.

The bottom line is that the more California can push its residents to voluntarily change their water-use behaviors, the less painful adapting to the drought will be — and the more it will feel like a choice.

“It’s a big human behavior experiment,” says Fahlund.